Before we jump into anything, we take a look at one of the most – among other things – defining events in the Space History, which has a great influence on the sector to this day.

Before we jump into anything, we take a look at one of the most – among other things – defining events in the Space History, which has a great influence on the sector to this day.

The tragedy of the space shuttle Challenger temporarily restrained development and its opportunities at NASA (for example, the Hubble space telescope was delayed by 4 years). This is the root cause of the seemingly excessive and numerous protocols that have been used since then on the occasion of each mission and launch, be it crewed and uncrewed space missions.

This event put a completely new foundations for the NASA’ operation protocolls.

The Columbia tragedy brought the end of the Space Shuttle program, which ran from 1981 to 2011.

But what is the Space Shuttle?

The tasks of the space shuttle missions were, for example: building the space station, putting satellites and space telescopes (Hubble) into orbit.

Have you seen the Armageddon movie (1998 – back then it was still MIR up there)? Freedom and Independence were the two spaceships they launched with. Those are the shuttles. =)

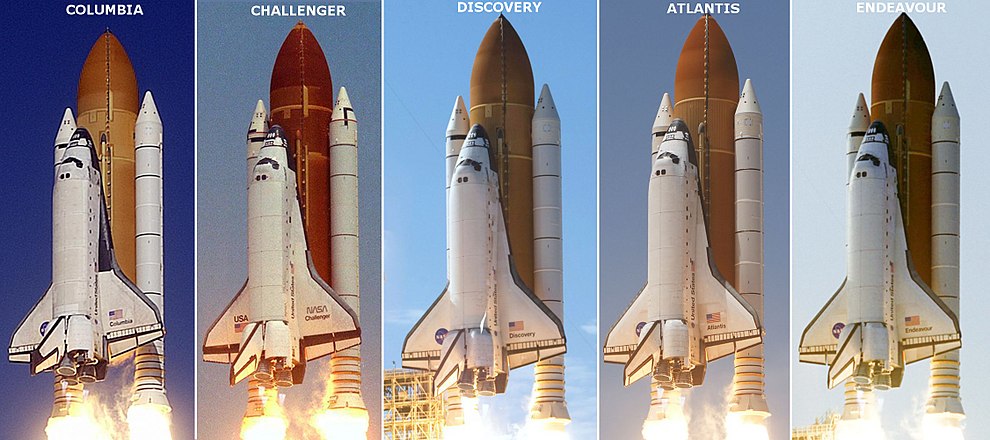

It’s a “2in1 machine”: spacecraft and airplane, some parts of which can be reused over and over again. It consists of 4 parts: the orbiter itself, main engines, an external fuel tank and 2 solid-propellant boosters. The external tank is the only one that is destroyed after separation, having completed its task (those nice colored ones in the picture below, on the “belly” of the shuttles). It is the last to detach from the orbiter. After disconnecting, the 2 boosters descend back into the ocean with parachutes. They are lifted, transported, then disassembled and reassembled.

The space shuttles did not have rescue systems (catapult seat, etc.) like other spacecraft intended for human travel.

The first space shuttle “prototype” was named: Enterprise.

And what is solid – propellants?

They are two – component materials (fuel and oxidizer) that, when mixed, produce a large amount of hot gas, which provides thrust.

THE CHALLENGER TRAGEDY

“My God, Thiokol! When do you want me to launch? Next April?”

Next day seven people lost their lives just 73 seconds after launch.

The question was posed by Lawrence Mulloy, head of solid rocket development at the NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, during a conference call to the manufacturer of the rocket’s sealing ring.

One of the most… If not THE most famous shuttle in the history of the Space Shuttle Program, is the CHALLENGER. Its tragedy was a huge blow to all of us in every way.

On January 28, 1986, just 73 seconds after launch, the rocket exploded in the troposphere (at this altitude, passenger aircraft still fly). Six astronauts and one civilian on board the space shuttle died when the crew cabin crashed into the ocean.

The launch was postponed several times.

First, it was delayed twice because of another mission, then because of possible unfavorable weather. Finally, on the 27th, there was a problem with the hatch on the deck, and by the time it was fixed, the time of day had become unfavorable for launch.

On the day of launch, it was delayed by two hours due to strong crosswinds.

A problem with the solid – propellant rocket was already noticed in previous flights, which was also reported and documented (1977).

This is the rocket that “pushes” the space shuttle itself to the Kármán line (altitude: 100 – 120 km), and then separates from it.

The rubber sealing ring called the O-ring, used for joints, is used to prevent high-pressure gases from escaping from the inside of the rocket at the joints. The rubber hardens under the influence of cold, becomes inelastic, and can break.

The temperature was minus degrees in those days – the night before launch it was – 8 C° – and the launch also took place at minus degrees.

In this case, this is what happened. As a result of the above, part of the O-ring burned from the hot gases. Where the seal was lost, the hot gas erupted, piercing the casing, reaching the external fuel tank and exploding. The shuttle itself was shattered by the force of the impact. The crew cabin section was shattered by the impact into the ocean, and the two rockets were self – destructed so that they would not cause damage to populated areas if they deviated from their orbits.

This was the 10th flight of the Challenger space shuttle, the 25th of the program. After that tragedy none space shuttle had taken off for more than 2.5 years. Among many other recommendations of the committee set up to analyze the tragedy (Rogers Commission), the rockets were redesigned, and from then on the crew wore pressure suits during launch and return. It seemed that all the mistakes were eliminated, and the protocols are working.

Until 2003.

THE COLUMBIA TRAGEDY

This event marked the end of the space shuttle era.

On during the launch, February 1, 2003 piece of the insulating foam broke off and the shuttle break apart upon the reentry. Seven astronauts lost their lives.

During takeoff, a large piece of insulating foam broke off from the external fuel tank (the large, colorful, disposable tank near the shuttle’s belly), which hit the left wing and damaged a thermal protection panel (thermal protection bricks – RCC). The problem was detected and, after some analysis, it was finally declared harmless down here.

However, upon reentry, hot air flowed in through a gap in the wing that had formed during takeoff, caused by the insulating foam. The extreme environmental factors weakened the wing from the inside, which broke off. This was the cause to loss of the shuttle and the crew.

NASA management did not make bad decisions arbitrarily or through negligence, but rather had considerations that later proved to be more emotional than rational.

For example, everyone firmly believed in the durability of the heat shields, especially the Reinforced Carbon-Carbon (RCC) elements used on the leading edge of the wing.

Astronaut Charles Bolden, later administrator of NASA, said the following:

“Interestingly, never in my memory—and I’ve been through my notebooks and everything—never did we talk about the reusable carbon-carbon, the RCC, the leading edge of the wing, leading edge of the tail, and the nose cap itself. Nobody ever considered any damage to that because we all thought that it was impenetrable. In fact, it was not until the loss of Columbia that I learned how thin it was. I grew up in the space program. I spent fourteen years in the space program flying, thinking that I had this huge mass that was about five or six inches thick on the leading edge of the wing. And, to find after Columbia that it was fractions of an inch thick, and that it wasn’t as strong as the Fiberglas on your [Chevrolets] Corvette, that was an eye-opener, and I think for all of us.”

The other reason, perhaps even less technical, was what guided NASA leaders in their decision-making. The risk management process was greatly influenced by the belief that there was nothing they could do if damage was discovered. This belief was expressed at the time by Jon C. Harpold, the director of operations:

“You know, there is nothing we can do about damage to the TPS. If it has been damaged it’s probably better not to know. I think the crew would rather not know. Don’t you think it would be better for them to have a happy successful flight and die unexpectedly during entry than to stay on orbit, knowing that there was nothing to be done, until the air ran out?”

After the Columbia tragedy in 2003, NASA shut down the space shuttle program in 2011.

The reason why the shutting down took so long is that no alternative was found to replace the shuttles, but they were still needed for Hubble, the ISS and other missions. And, as in the case of Challenger, not a single space shuttle took off here to for more than 2 years.

A lot of documentaries, online articles, official data and reports about the space shuttles and their missions can also be found. By surfing through NASA’s website, we can find a lot of material (not only) about the above, such as:

https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4225/documentation/hsf-record/hsf.htm#shuttle

https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/shuttle/shuttlemissions/archives/sts-51L.html

https://history.nasa.gov/columbia/index.html

Be a Nerdy Bird!